First Look: 2024 Santa Cruz V10 & Suspension Chat with 'The Human Dyno'

Continually improving products is no simple task, especially when they’re as sought after as the Santa Cruz V10. The Santa Cruz Syndicate has been testing this platform for nearly two years and raced the entire 2023 season aboard the bike, however, it wasn't available to the public. Across the team, riders are diverse in height and the tallest of the bunch, Greg Minnaar, has been sticking with a full 29er, while the others preferred a mixed-wheel setup.

Now, in its eighth generation, the popular downhill bike’s geometry and suspension kinematics have been highly refined, yet still offer customization without complex packaging. Although there’s been a heavy influence from the Syndicate team, Santa Cruz is adamant that the bike can still cater to bike park enthusiasts whose idea of fun may not always be going as fast as possible.

Now, in its eighth generation, the popular downhill bike’s geometry and suspension kinematics have been highly refined, yet still offer customization without complex packaging. Although there’s been a heavy influence from the Syndicate team, Santa Cruz is adamant that the bike can still cater to bike park enthusiasts whose idea of fun may not always be going as fast as possible.

Santa Cruz V10 Details

• Frame material: CC carbon

• Wheel size: Mixed (size SM-LG), 29 (size XL)

• Travel: 208mm

• Head tube angle: 62.7, 62.9, or 63°

• Reach: 419, 454, 474, 499 (+/- 5mm)

• Chainstay: 445, 450, 456, 461 (+/- 5mm)

• Weight: N/A

• Pricing: $6,799 - $8,599 / Frame only: $3,799 USD

• santacruzbicycles.com

• Frame material: CC carbon

• Wheel size: Mixed (size SM-LG), 29 (size XL)

• Travel: 208mm

• Head tube angle: 62.7, 62.9, or 63°

• Reach: 419, 454, 474, 499 (+/- 5mm)

• Chainstay: 445, 450, 456, 461 (+/- 5mm)

• Weight: N/A

• Pricing: $6,799 - $8,599 / Frame only: $3,799 USD

• santacruzbicycles.com

Fully-guided internal cable routing, fenders, integrated fork bumpers and plenty of geometry adjustments look to make a very well thought out 8th generation V10.

Frame Details

Two elements of the frame were made clear from the start though: the carbon construction and the continuation of the VPP suspension. An all-new front triangle was apparent by the split-tube seat mast, which does bring a structural element to the design - there’s more on that and the suspension later down the page.

Included in that new front triangle is an adjustable reach headset cup that comes stock with the frame. There are also two more adjustments to be found on the V10.8 - a chainstay length adjustment at the rear axle, along with a sliding brake mount, and a lower link geometry adjustment.

Other less-apparent, but still highly respectable items are the integrated fork bumpers, downtube protectors, rear fender, and fully guided internal cable routing that features additional external guides at the lower pivots.

Suspension Design

If you were following along with Santa Cruz’s video series that covered the development of the V10.8, you might have heard their exploration around a virtual high pivot, but through timed testing and qualitative feedback, they decided to stick with their traditional Virtual Pivot Point suspension (VPP). There’s also a slight drop in travel from 215 to 208mm.

Visually, not a lot has changed, however, listening to the team rider’s first impressions on the new bike, those tiny tweaks were highly welcomed - less pedal kickback and more support were notable attributes.

We got in touch with Kiran MacKinnon, one of the engineers at Santa Cruz, often called “the human dyno”, to ask if he could relate what the suspension looks like on the drawing board to what riders are feeling on the trail.

Matt: What are the major differences between the new bike and the previous generation encompassing the suspension kinematics, frame construction, and geometry? How do those changes translate on the trail?

Kiran MacKinnon: The V10.8 frame is entirely new, and all areas mentioned are designed around new goals. Leverage, anti-squat, and anti-rise were all heavily scrutinized to achieve what we think is the best balance of traction and support. The frame construction differences are mostly a result of packaging the new linkage and achieving reduced frame stiffness goals. Geometry was updated but not massively changed... Reach per size was increased, but otherwise, it was relatively small tweaks to address team preferences from over the years. We think everything combined translates to a bike that is more predictable and comfortable at the limit.

Matt: In the first episode of the bike's development video series, you (and Greg) mention how the previous bike generated speed and cornered exceptionally well. What can you attribute that to?

Kiran MacKinnon: I think this goes back to our goals when it comes to leverage, frame stiffness, and axle path... where the line is drawn between comfort and performance on each.

Matt: How did you maintain those positive characteristics of the previous bike while making other changes?

Kiran MacKinnon: That part was challenging, mostly because there's a lot of comfort in familiarity from a racer's perspective. The whole team was pretty happy with V10.7, so there was an emphasis on not losing the bike's character. There were a few easy wins when it came to anti-squat and anti-rise for sensitivity, but for things like leverage, geo, and stiffness, we tried to only make changes that we thought brought a higher quality experience, and tried to stay away from too many trade-offs. Lots of small changes equated to a larger change in quality than in character, at least that was the hope.

Matt: Moving on to the second video in the series, Jackson's first takeaway was how much smoother the new bike was. What do you think he means by that? Is there more small bump compliance, less brake squat, and/or lower chain feedback?

Kiran MacKinnon: A large part of that sensitivity is due to a flatter, lower starting leverage paired with significantly reduced anti-squat and pedal kickback. Reduced frame stiffness aids in the grippy feel, and lower anti-rise helps keep things working under braking.

Matt: Nina says the bike rides higher in the travel. Would it be correct to say then that the 8th generation V10 has a more linear leverage rate?

Kiran MacKinnon: Yeah, the new bike has a straighter (more linear) leverage curve that is also less progressive. Most of the ride height improvement is due to the bike's lower starting leverage ratio.

Matt: I often hear the phrase, "It's an easy bike to ride." Laurie says nearly those exact words after a first lap. What would you associate that quality with?

Kiran MacKinnon: I think it's just a matter of refinement... Taking the good from the old bike's recipe and giving it some extra sauce. Not doing anything too weird or goofy just for the sake of making the bike seem reinvented.

Matt:Where do you draw the line between a bike having too much support versus enough small bump compliance? How much of that is reliant on the rear shock?

Kiran MacKinnon: It's always a balance. When working on linkages, I'm constantly trying to get the bike's travel to feel consistent from top to bottom. No peaks or valleys in terms of support or feedback. Doing this correctly helps a lot to reduce compromise when finding the balance of support and activity with shock tuning/setup. I think everyone has a preference when it comes to this topic, but I think a well-executed linkage gives the rider the ability to draw their own line with shock setup and have a quality experience.

Matt: Jackson, Nina, and Laurie are all mentioned the increased support, grip, and control during the setup in Queenstown. They're all elite-level athletes though. How do those changes transpire for average riders and is there a compromise there to give the team riders what they need?

Kiran MacKinnon: This plays pretty well into my previous comment. Especially when the bike's use case is clear, I think it's possible to make a linkage that feels high quality and also accommodates different support vs activity preferences.

Matt:Talking purely in terms of timed testing, does that mean, in theory, that the fastest bike might not always be the most comfortable bike?

Kiran MacKinnon: That's where things get blurry depending on what comfort means to you... I do think the bike that makes the rider feel most comfortable when pushing the pace is always the fastest bike. However, I don't think the squishiest bike is usually the fastest.

Matt: Finally, is the new split-tube seat mast all about identifying the bike as the newest version, or is there more at play there?

Kiran MacKinnon: The split helps support the longer seat mast due to the linkage/shock being pushed further forward in the frame for better kinematics.

Geometry

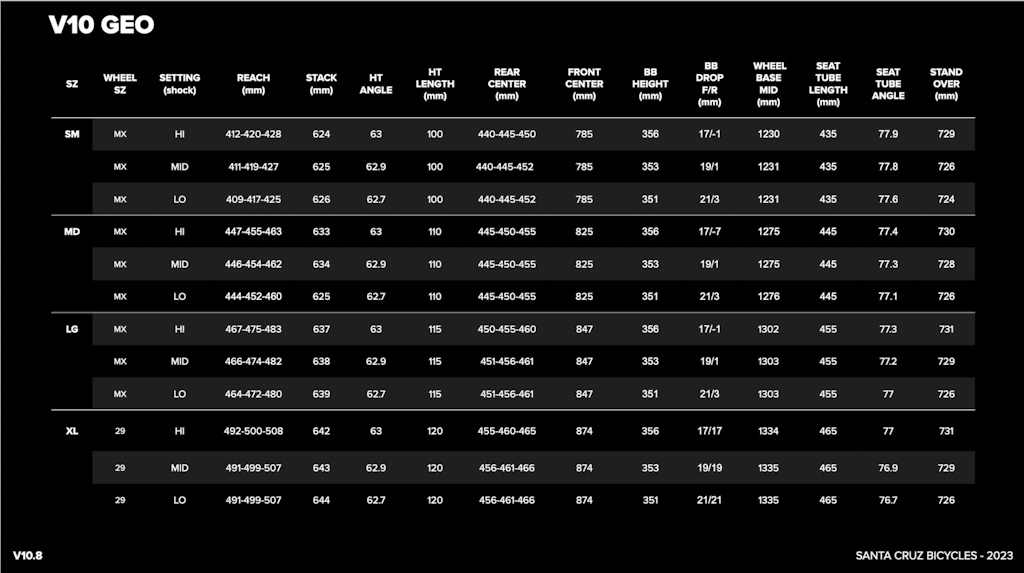

We mentioned the frame components that allow for the geometry changes, but what exactly are those numbers? For starters, there are four frame sizes; SM, MD, LG, and XL. All frames run exclusively on MX wheels, except the XL, which rolls on a full 29er chassis.

The Syndicate team had been using offset headset cups in the previous frame to dial in the reach for some time, whereas the new frame captures its own cup system to offer a zero or 5mm fore and aft adjustment. Starting with the smallest frame in the neutral position, those reach numbers are listed at 419, 454, 474, and 499mm.

Similarly, there’s a chainstay adjustment at the rear axle that allows for the same amount of movement. Each frame has a tailored rear center starting at 445, moving up to 450, 456, and 461 for the XL. A sliding brake mount means that you don’t need to carry alternates if you want to switch that chainstay length and is one less part to lose.

Depending on the track steepness, riders may want to modify the BB height and head angle. Santa Cruz has carried over the flip-chip adjustment on the lower link to do just that, except there are now three head angle positions of 62.7, 62.9, or 63 degrees.

Pricing, Specs, and Availability

Santa Cruz is offering the V10 in two build options, the $6,799 DH S and the $8,599 DH X01, both with the CC carbon frame.

As for the build kits, the main differences lie in the drivetrain, brakes, and suspension components. The DH S build includes a Fox 40 Performance Elite fork and Performance DHX2 shock, SRAM Code Stealth Bronze brakes, GX DH shifting and Descendant cranks.

On the higher end DH X01 build, the suspension steps up to the Factory Kashima level at both ends, Code Stealth Silver brakes, and the X01 DH drivetrain.

Both kits come with Reserve 30HD alloy wheels, OneUp Components alloy bar and direct mount stem, and Maxxis Assegai tires.

Author Info:

Must Read This Week

Yeah, I went with the 2002 Intense M1 and a 2002 Japanese/RHD Honda Integra Type R that fits 2 DH bikes, gear, tools, and luggage for 4 days at Whistler in the rear hatch with the seats laid flat. Both still run like new (unlike my body, sadly). 8400rpm with the music cranked on the way to Snoqualmie or Whistler is a great warmup for DH laps =)

www.pinkbike.com/photo/25834816/?s6

www.pinkbike.com/photo/25834817/?s6

www.pinkbike.com/photo/25834818/?s5

Now I just need a matching 2024 red Intense M1 and a matching 2024 blue Integra Type S or blue Civic Type R, both of which fit DH bikes in the rear hatch with the rear seats laid flat. Good work, Honda (and Intense and Santa Cruz)!

www.pinkbike.com/buysell/772777

As an older fella I thought I’d treat myself to a M1 after all these years and planned on ordering on …. Until this came out.

Decisions …

The Santa Cruz "warranty" isn't a warranty, its basically an insurance, which is why its not transferrable. Most every big name carbon manufacturer outsources production where the assembly of the layups is done by humans with cost savings in mind, so you get mistakes in frames like voids or delaminations. The business case is that certain percentage of frames are going to fail, which get replaced under the bought insurance policy included in the higher cost of the bike.

And that is if Santa Cruz deems the failure as a warranty issue. Its not uncommon for all the big brands to deny warranty claims because they believe its improper use.

In terms of dominant dynamics, bike riding is mostly your body mass, suspended by the primary suspension components that are you legs and arms, with a bike suspension being there for a much faster response rate than your legs arms to absorb bumps

So while there are differences, most performance of a bike is coming from you. And most any bike you can set up to perform in a specific way. You got used to the current bike that you ride, and there isn't really a guide that THAT specific geometry is correct. So along the same lines, you can get used to another bike quite easily with time riding it.

If you are a high level racer and know what you want, the story is of course different, but like I said, most people would enjoy a compliant steel heavier DH bike over any of these, even if it doesn't seem so. You will get more laps in a day because you are less tired, gain more confidence to hit steeper/rougher trails, carry speed easier, e.t.c.

Without C-scanning the carbon frames, you cannot be sure of build construction, so you cannot be sure of build quality. Santa Cruz frames do crack, because of the errors in introduced during layup that can be present in most carbon bikes out there. There is no way to ensure perfect layup quality unless you bring all your manufacturing in house.

And btw, Aluminum can be f*cked up as well, ask people with Commencals.

Now personally, I wouldn't pay a premium for a product like this, even if the defects were minor enough not to cause frame damage. If the carbon bikes were priced in line with others, I would have no issues.

As far as Canfield goes, they have a reputation in building pretty burly, heavy dh bikes, which don't really fail. They have had issues with failing trail bikes in the past though, so they aren't fully clear, but like I said, Jedis seem to be bombproof.

I would also argue against your statement where "most people would enjoy a compliant steel heavier DH bike over any of these" for the exact same reasons.

I've ridden many frames and suspension designs, and found what I like and what works well for me. I would also note that many of the people I have had the luxury to race with have had almost identical platforms with entirely different setups in ride charictaristics. Also why slwere seeing bikes with more and more adjustability.

"Compliance" is a word that is so freely thrown around in the bike industry.

It's also something that is so subjective.

This is the beauty of having so many great options in this industry. Otherwise everybody would be riding a big heavy "compliant" steel frame.

I would however like to understand further what your definition of compliant is?

The V10 has had a great reputation as a reliable bike, so much so that I would argue that SC has one of the best warranties in the business.

If at any point you feel a valid argument is "there are more SC bikes that have cracked than Canfield". Well there are more stolen Honda civics than Bently continentals. There's also alot more.

I mean none of what you said is false, but you are missing the point. Would you rather ride:

- Overbuilt bike that doesn't crack for less money

- Bike that can crack for more money.

The choice is pretty simple IMO.

>Ive ridden many frames and suspension designs, and found what I like and what works well for me.

I don't know if you realize this, but unless

- You did timed back to back runs

- You used similar suspension components, tires , e.t.c

- You et up the effective reach and stack exactly the same.

Then the determination is utterly pointless. If you are going by feel, i.e.e what feels good, your feel is extremely subjective. If you get a V10 as your first bike, and you feel good that you are brand new shiny bike that is used to win world cups, yo can get get a dopamine rush that may cause you push harder and ride faster, which will result in you believing that the bike is better than the rest. This is literally the whole point of marketing which is why competitions and sponsored athletes exist in the first place, to convince buyers that their bike is better than the manufacturers.

On the other hand, you look at things objectively, bike suspension platform and layout pretty much don't matter as much as people think. As long as the geo is in the ballpark for DH riding and you have 200mm of travel, you can ride it just like any other bike. There is evidence of this too, you don't see any factory dominating, you see good riders dominating on sponsored bikes that are set up for them, and then next year someone else takes over.

As for steel, its well known that steel bikes are more flexy and comfortable. Neko and Asa confirmed this pretty much fully with their steel framed version of the Frameworks dh bike. If you want to get the most pop, thats certainly your choice, but realistically you are probably not up to the skill fitness level that either of them ride at, and its better for you to get something that is more comfortable and less pingy, because that is proven to increase endurance.

I will continue to disagree that a bike is as simple as it's geometries, and again because your statement that says it is was directly contradicted by you stating that frame material makes a difference.

Geometry is one thing that does play a roll yes, but what about anti squat? How about antirise? Leverage rate? Word of the day, "compliance". Again going back to SC vs Intense, simmilar designs yes polarizingly differant. Also would you say that a 200lbs rider would benefit from the same level of "compliance" as a 150lbs rider?

What were also seeing with factory bikes is ALOT of non production parts to get the bike to perform the way the rider wants.

I can say for certain (Because I have ridden many different designs back to back) that there are allt of differences between most brands, I genuinely disagree in a blanket statement that "As long as the geo is in the ballpark for DH riding and you have 200mm of travel, you can ride it just like any other bike", because I know this to be untrue as an absolute fact.

I think Canfield make great bikes, and they definitely have their following, alot like Zerode and Knolly, but I don't think the answer is "An over built bike".

Why do people chime in with their opinions with incomplete information?

the lust for a new Civic type R, well I can only assume youre eyesight has deteriorated to the point that you prolly shouldnt be driving or riding!

Edit: Found prices:

Frame $3800 USD / £3999 GBP

S build $6800 USD / £6999 GBP

XO1 build $8600 USD / £8999 GBP

I know quite a few people with repaired carbon bikes. All still in service AFAIK.

Frame $3800

Entry build $6800

Xo build $8600

You’re knocking something before you’ve even tried it.

Also, the reach adjust is plus minus 8mm, not 5mm.

Aside from needing to pedal to the top, are there any downsides to the DH bike while descending? Is a DH bike as fun on some of the flatter bike park trails and an enduro bike would be?

In seriousness though, whilst to me the v10 feels quite playful for a dh bike, it’s still a dh bike and it needs speed to come alive. Flatter trails will be dull compared to an enduro. The side hits you popped off on a trail bike will cease to exist on the v10.

That's because long travel is good at carrying speed (not slowing down), and short travel is good at generating speed (speeding up). Imagine riding a rigid bike and then a DH bike on a pumptrack- the DH bike is terrible at generating speed. Now imagine riding both of those bikes on the Canadian Open track at Whistler- the DH bike is so much easier to carry speed on. When people talk about long travel bikes as if the only trade off is uphill climbing, it makes me want to beat my head against a wall.

Having said all that, there is absolutely positively no substitute for a real DH bike on the right terrain. It's the most fun you'll ever have on a bike. The question is whether your local bike park actually has good DH terrain, or just trail bike stuff. Most bike parks don't.

"transpire" doesn't make sense: "how to those changes _occur_ for average riders"? They occur the same way: the bike changed. Perhaps you meant "translate", or "transcribe?

Are there any (recent) bikes with CS adjustment that require swapping brake mounts? Everything I recall seeing lately either slides the whole post-mount _with_ the dropout, or allows sliding the mount like this one.

Different cable routing wow!!!!

"more linear" and ALSO "less progressive"... So linear-ness and progressive-ness aren't directly connected, like they always are implied to be?

Is Kiran saying that "progressiveness" is just the difference between starting and ending ratios? Has nothing to do with the rate of ratio change at certain points? Because you can have a huge number of curves that have matching starting and ending ratios, including the idealized "linear" straight line direct from start to end, and they will all feel different.

Linear is the general shape of the curve and how progressive it is, as typically defined (badly) by mountain bike companies is % difference between the initial rate and final rate.

“% progressive” is a really bad way that bike companies talk about their leverage rate and it leads to bad narratives (see recent unno burn review).

And if you want to be clear, Trek won 4 WCs and a world champs.