Review: How Canyon's KIS Could Change Mountain Biking, and Why It Probably Won't

Canyon's bike seems to be branching out into each and every direction. Whether it's conservative or extreme geometry, simple elegance or quirky, kooky features, the German brand has the eventuality covered. In some ways, they really are becoming the brand for everyone, because they seem to make everything, for both the good and the bad. Do you want an enduro bike that takes new school reach numbers to post-modern surrealism? Here, have the Strive. What about one of the most pragmatic downhill bikes specced with a wish list of sensible features? Here, try the Sender. Clean cut and simple, shred bike, what about the Spectral 125?

KIS Details

• Available on Canyons & Litevilles

• KIS stands for "Keep It Stable"

• Will always return your wheel to center

• Claimed weight of 110g

• Tested on Spectral CF8 Large

• Adjustable but undamped system

• canyon.com

• Available on Canyons & Litevilles

• KIS stands for "Keep It Stable"

• Will always return your wheel to center

• Claimed weight of 110g

• Tested on Spectral CF8 Large

• Adjustable but undamped system

• canyon.com

I love this wacky and wonderful approach, and at their core they clearly have an incredibly passionate design team who are looking to try just about anything to make bikes that are different, that are effective, and that stand out from the crowd. And isn't that what it's all about? In fact, the progression within the brand, and subsequently the place it holds in the wider market, has been turbocharged. They've arguably out-innovated most other big brands even if that has involved some duds along the way, all the while expanding their range drastically.

Recently, they've incorporated Syntace's KIS (Keep It Stable) system. Liteville is also in on the project, but if you're at all likely to see it at the local trailhead I imagine it would be on a Canyon. This system is housed rather neatly inside the top tube and aims to stabilize the steering. The idea is that with a sprung element always trying to steer the front wheel straight ahead, you're less likely to feel the negative effects of wheel flop plus, or so it's claimed, benefit from steering that is less twitchy, better weighted, and subsequently more predictable.

What Is It?

Inside the top tube are two small springs that are tethered to a cam which is cinched on the steerer via a a bolt that can be accessed through a small hole in the top tube. As you turn the bars and rotate the steerer, they turn the cam which in turn pulls on the springs (although there are two springs, they're not for left and right but are rather engaged in unison). This means that as you turn the bars, the springs stretch, and as they return will always try to return the wheel back to center.

Much like in a suspension linkage, the mechanics of any lever, spring, or cam are designed with certain parameters in mind. In this instance, the geometry of the Kevlar bands that attach the spring to the cam, and the shape of the cam itself, give a particular torque curve. This gives the torque curve in the above graphic. Initially, the springs take on quite a lot of load, but as the bars turn past 15 degrees, the rate in which the system takes on load decreases. Meaning that the initial part has a greater returning force for the amount that the fork steerer is turned than the latter part.

It should also be noted, especially when you consider my ride impressions, that this isn't a steering damper, nor is it a system that is damped at all. It's just a spring trying to straighten the wheel, whereas a damper controls the rate the bars can turn by forcing oil through a circuit. This means that the system can take up energy quickly and, to my mind, dump that energy quickly too. This becomes more apparent in the different settings thta can be adjusted via a sliding mechanism and a 4 mm Allen key on the top tube.

The KIS system isn't a steering damper, but they are still out there and they can aid riders with particular demands. (Photo credit Tommy Wilkinson)

What Problems Is It Trying to Solve?

In Canyon's copy, they write about how most other vehicles, be it planes, cars or even boats, have a device to self-center their steering. I would contend, however, that none of these weigh 25% of the user's weight and rely heavily upon being leaned to efficiently steer. Either way though, it's clear that Canyon and Jo Klieber of Syntace, who originally designed the system, have been looking at places other than the bicycle industry for inspiration.

How I initially interpreted this system, and its impact on the bike, changed somewhat as the testing period went on. In the First Ride article, Seb Stott goes into detail explaining geometry's relationship to wheel flop and its influence on our bikes, and how the system sets out to solve several problems that have long persisted in cycling.

Seb wrote "This torque is designed to counteract the force created by a phenomenon called wheel flop. If you stand your bike upright with the steering off-center, the handlebars will naturally turn away from straight ahead, towards a steering angle of 90 degrees. This is because, as the steering angle increases, the bike frame (and with it the rider) drops towards the ground - by over 10 mm in the case of a slack bike.

"To picture this, imagine a bike with a 0-degree head angle (a horizontal fork). Now as you turn the handlebars away from straight ahead towards 90 degrees, the head tube would drop towards the ground by the radius of the wheel. With a vertical head angle, the head tube wouldn't drop at all. So the slacker the bike's head angle, the more the head tube will dip as the bike steers.

"This drop in head tube height creates a force that acts to pull the steering away from straight ahead. This is a destabilizing force because (within the range of normal steering angles) the further the steering moves away from straight ahead the more force acts to pull it even further away."

To my mind, the sensation of stability is a consequence of how a rider's weight is held by the chassis. Suspension, wheel size and speed notwithstanding, it's the result of geometry and dimensions of key components. The problem with geometry is that it's inherently limited by largely being the expression of a rider's weight, and the impact of dimension changes to affect where that weight sits between two axles, both in terms of fore and aft and also height. The exciting thing about KIS, or something similar to it, could be its ability to add another frontier in the quest for stability, or indeed open up another avenue in how to balance the compromise between stability (the ability to resist external forces) and balance (the distribution of weight between one or more points).

Personally, I like a bike that has a great deal of balance first and foremost, and then subsequently works out how to integrate stability within that, rather than a bike that is incredibly stable but feels a little dull or cumbersome as it resists both inputs from the rider as well as feedback from the trail.

During my period of testing, which included riding two identical Canyon Spectrals back to back, one with the system and one without, KIS felt like something that was trying to break away from the limitations of geometry, and the oftentimes inherent trade-off that occurs when we make a bike more or less suited to one particular application. It feels like a way to incorporate better-behaved climbing characteristics when you have a geometry that gives a light front wheel on steeper sections and a way to isolate that away from the complications of slacker bikes.

I would contend that when we make any change to geometry that makes it more positive in one direction often has a negative consequence in another. For instance, our slack bikes have steep seat tubes, which can be great, but there's a reason road bikes don't have 78-degree seat angles, and that's because what might feel good on a steep fire road can feel pretty horrible on a flatter one, and has a tendency to overload the rider's wrists. Similarly, while I am a fan of long rear ends, they can make it harder to execute certain maneuvers, especially at lower speeds. A system, such as KIS, would be able to increase stability on the front wheel in these instances while also isolating them away from geometry changes such as these.

Although speculative on my part, the fact that this system is included in a pre-existing Canyon model is noteworthy. There are probably better candidates, geometry-wise, to feature this system to reap the supposed benefits, or better yet it could have had an entire bike built around it. I think if that were the case, the initial copy in the release may have read a little differently. I would be curious to see this system on a bike with some real outliers in terms of chainstay length, head angle, trail, or fork offset. Maybe we should put it on the Grim Donut?

How Did I Test It?

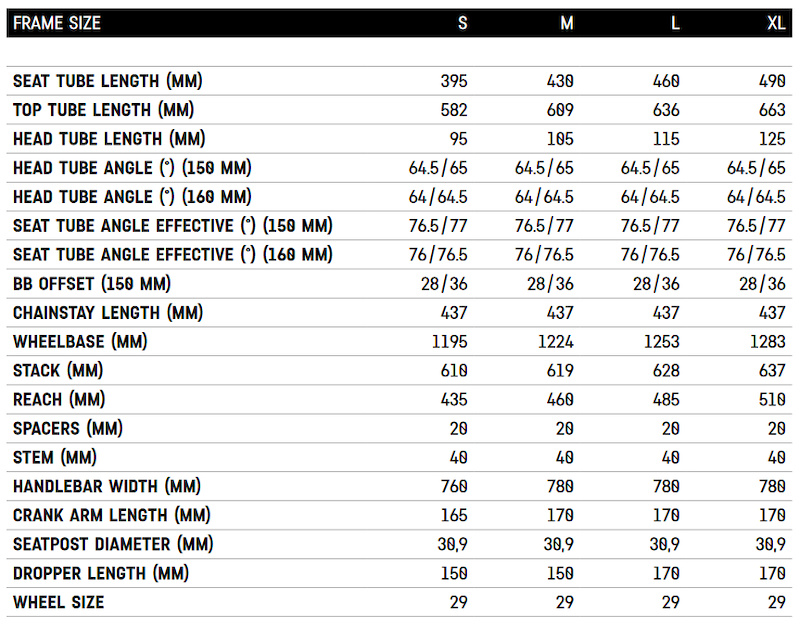

For this test period, Canyon sent me two Canyon Spectrals in the same size and spec. As a tester, this is something of a treat and the perfect way to isolate or test one particular change. Mike Kazimer has previously reviewed the Spectral, which you can read about here.

During testing, I rode the bikes back to back many, many times. That consisted of longer ninety-minute rides of around 800 m over elevation change where I could get settled within the bike and really compare notes over the course of a more typical ride on both climbs and descents and back-to-back runs at Whistler Bike Park. The bikes were set up in the exact same way and I ran the same tires, cockpit settings, and pressures throughout. My preferred setting was the one with the least preload on the springs.

I have seen some Canyon athletes running KIS, and I would be curious about the level of force provided. Every time I lessened the system's influence it improved the handling. Maybe there is a setting less that the lowest-preload setting, but more than absolutely 0 that could help better cherry-pick the good bits and do without the bad.

Ride Impressions

Swinging a leg over the Spectral it immediately becomes very apparent that there is something different going on with your bike. The device has three marked positions on its sliding scale. Sliding the hardware along changes the preload on the springs. I tried it in all three marked positions and found it dominated the feeling of a bike in the more extreme positions (middle and max). The way we steer our bikes can often be initiated by a countersteer. This system wants to kill that gentle input dead. This has some consequences. Firstly, riding a bike without your hands is terrifying. Secondly, it takes some relearning of how you initiate turns. Thirdly, and quite oddly, I felt that my brain is so hardwired for a set outcome to the inputs I put through the bike that on two occasions I got seasick while riding this bike on long climbs. My balance felt like it wasn't connected to what was happening with my body, similar to the feeling that occur when you're on a boat your balance isn't lining up with how your eyes perceive the world, .

This system shines on the climbs. The act of reducing the effects of wheel flop had a large effect. If you were climbing something steep and technical, instead of feeling an element of instability as you pushed your front wheel up and over a square edge or root, it felt like it acted more as an anchor. The KIS system makes the bike feel like it has a set of stabilizers or training wheels on the front axle. This was massively noticeable on climbs, and the more heinous the climb the better it got. It feels reassuring on tech, and on particularly steep or loose sections it means you can ride with more weight over the rear to generate more traction. This becomes particularly useful when grip is limited in the first place. I didn't have to balance the demands of the front and rear wheels, and I could just concentrate on delivering consistent traction to the rear.

It doesn't undermine the great things about the easy-going Spectral but I'm not sure it enhances them either.

On the descents, however, it was a different story that wasn't to my taste whatsoever. The times I disliked it least was when I noticed it less. For instance, in large radius berms they are more about leaning the bike than turning the bars. As a general rule, the tighter the turn and the more extreme the steering angle the less I enjoyed it. This became particularly apparent in sequential turns that rely upon you loading up the bike. The way that the system dumps off a higher rate of torque as it returns to center before picking it up again at an initially high rate meant that going between tight steep catches felt like high-siding was always a distinct possibility. It felt like it was hooking up my body weight much in the same way that a fork that rebounds too fast from deep in its stroke only to hit another edge can feel like you're getting double-bounced. My body weight was overloading the system, and in my opinion the only way to negate this issue is damping.

The way the bike returns the center of its steering is something I don't often think about, but with this system, I was so conscious of it, and really disliked the variation in the torque ratio as it ushered me back to center in a hurry, before I felt the resistance of the system as I moved through the center and it picked up tension on the other side.

Not everyone is the same when it comes to adaptability, but on anything but the lowest setting I ran into issues. It wasn't just riding the bike, which you do learn relatively quickly, but also coming back to riding normal bikes. Suddenly, it just felt like I lost my frame of reference for how I wanted a bike to hold my weight.

I'm not convinced by KIS, and would argue simple cockpit adjustments to suit the rider have a far greater and beneficial impact for most mountain bikers.

What's It Like to Live With?

Canyon has done a great job of integrating this into the top-tube of the Spectral, but it's not a perfect solution. There are some quirky problems that mean you have to think more about some basic everyday occurrences. Leaning the bike by the rear wheel tends to be more problematic, and storing it with other bikes can be more difficult as the bars only want to go straight ahead, which can make having several bikes in tight storage tricky, and it's an extra layer of complication for packing it up or fitting it in a car. Each one by itself isn't a deal breaker but together they do become quite irritating.

Where Do We Go From Here?

I didn't like the KIS system, and there's little to no point suggesting otherwise. However, I do genuinely commend the idea. I don't think the Spectral is the right place for it, but I would love to see it integrated from the ground up in some extreme gravity designs or, moreover, built with some level of damping. I really feel damping this spring would help make good on the claims of a greater level of connection between the front and the rear of the bike, or at least I'd be curious to try. It's not so much on the way the spring takes up load, but rather the way it returns that energy to the rider. It sometimes felt erratic and chaotic, and some kind of rebound damping could be a way to solve this issue.

Without damping I could see it having an application in XC racing. The increase in stability on the front means the rider can grant more grip to the rear wheel, especially when traction is low. Yes, there is a small weight penalty of around 110 grams but that would be worth it if it saved a World Cup rider from having to get off and run with their bike even once.

Either way, keep it wacky, Canyon. I don't think this is the answer but I respect the effort.

Pros

+ Gives a very stable front end of climbs+ Incorporated well into the frame

+ Can let the rider focus on ensuring the rear wheel is gripping

Cons

- Can feel detrimental on tighter trails, or steeper sections- Adds another layer of feedback to react to while riding

- A damped version would possibly be better

Pinkbike's Take

Author Info:

Must Read This Week

Btw, anyone remember the power balance scam?

Yeah!

Let's all go back to 26" wheels and elastomer sprung suspension. All of this high tech bullshit that makes our bikes considerably better to ride is far too uncool.

www.pinkbike.com/news/cross-country-tech-vallnord-world-cup-2017.html

With the former you load up your bike with loads of stuff, in side panniers, often front and rear, and loads more on top of the racks. It lets you travel by bike, but all that weight and volume severely limit what you can ride. It's mostly slow and steady riding on roads and/or wide gravel roads. The bike is purely a means of transportation.

With bike packing you limit what you take with you as much as possible, and strap that stuff as close as possible to the bike itself. That way you can still ride fun trails, and stay away from roads and traffic. Now it's just fun riding for days, with the stuff to sleep at night in between.

Yes, it's a bit hyped (and the name is kinda stupid), but it's fun as helle and a whole different beast than the old bike touring.

More capable, yes, but often also less fun. Modern full sus bikes on less demanding trails can be like ride a tank over a twig. Where's the fun in that?

There's also lots more stuff to maintain and adjust, and to pay for of course. I don't know (or care) if my full rigid '94 mtb is (un)cool, but it is as simple as it gets, costs almost no time or money to maintain, and it's fun as hell.

I disagree, it definitely makes bikes objectively better to ride.

Subjectively maybe not, but I think you're in a pretty small group of people if you don't enjoy riding modern bikes more than old ones. It really depends where you're riding though - yes people rode the trails here on the North Shore on old hardtails, but NOT ONE person I know who's been around since the 90s wishes they still had an older bike like that.

Actually maybe Andrew Major, but he's a bit of a kook.

'Better' is not synonimous to 'more capable' or 'more comfortable'.

My bike has been going strong ever since I bought it in 1994. It has gone through some iterations of course, but all in all it has cost me WAY less than buying new bikes every few years. It hardly costs me time or money to maintain it (and I can do all repairs and maintenance myself), it always works, and I always have loads of fun riding it. It demands my attention, requires skill to ride technical stuff, it's licht and nimble, and I love that.

Riding on a modern, full sus bike is very boing for me. Like riding on a mattress, it filters the riding feel for me. I don't like being occupied with operating a dropper post and the suspension lockout, it's a hassle.

So for me, my bike is way better than any modern one.

Have you tried slowing down your rebound? ;-)

I love underbiking. On a modern bike. With disc brakes. And suspension. And good geometry. And wheels that won’t fold in half if you look at them funny.

I ride the north shore on a 115mm travel 29er. I know what underbiking is. And it’s much more fun on a bike that isn’t 30 years old.

And on a rigid bike, things feel fast quite fast (no pun intended).

It's a bit like a go kart. Yes, there's faster vehicles, but riding a go kart is so much fun because it feels very fast.

Also, I haven't had one single wheel fold in my 35 years of mountain biking. 26" with 36 spokes, they can stand a beating.

@t-swing WE NEED ANSWERS

/s

Good answer

You say 'cargo bike', we say 'bakfiets' (instead of 'bak fiets').

We even connect English words when we use them in our language, like 'mountainbike' and 'bikepacking'.

So that makes it possible to string together a lot of terms for a very specific thing, to make a very long word, but that's not something that is actually used very often. It's not in the dictionary for that reason.

And no, I'm not joking.

And also elves… who live in the head tube and don’t like the sudden increase in tourism.

And I think Henry's well written and thoughtful article (haven't watched the video yet) does a good job of explaining what they're trying to do and why. What I'd love to read more about, though, is some consideration of the effect of speed and dynamic loading on stability and wheel flop and all that. Wheels create stability that increases with speeds, as they're big old gyros, and bottom bracket drop combined with dynamic loading creates stability that has a big effect on how stable/planted your bike feels. That, of course, is mostly a question of flat/gently rolling/descending trails - climbing is a different story.

I find all that Canyon talk about "other" vehicles interesting - they are talking about things that either are planted of four wheels (cars), or otherwise are subject to aero- or hydro-dynamics (planes and boats), but doesn't address motorcycles. You'd think that would the first place to go...

KIS is putting the cart before the horse.

I used the ride a Harley chopper (don’t ask me why) with a head angle slightly below 60 degrees, and it was not an issue.

The good thing is that humans get used to everything...

This sentence alone suggests that whoever wrote that copy for Canyon has absolutely no idea how bicycles actually work. This isn't just a solution looking for a problem, it's a non-solution that actually creates a problem.

This is why BMX and DJ riders are happier more fun people.

Williams racing doing a proper job

Did not watch the video. Did you ride with no hands? My cheap e cargo bike could use something like this, or a steering damper. It gets a serious death wobble going if I let go of the bars. I am not convinced it is beneficial on a well designed mtb.

But due to the nature of the rubber, it's a damped spring

www.pinkbike.com/video/580599

In general when handling the bike, like lean it or carry it, it is nice that the handlebar will not rotate freely.

When climbing steeps, it's a little easier to keep the balance.

And when going down, the most noticable thing was that when I locked the rear wheel it did not pivot around the front wheel as much. In general, I would say the system keeps the bike straight when a wheel loses traction. But I need more time on it to see how much this helps on the front.

Good thing is, I did not notice any adverse effect so far!

So, guessing the whoever wrote the ad copy hasn't ridden a bicycle, driven a boat, or flown a plane.

Excellent video, very informative, great descriptions (bit of a wander there with the fork and Meta, but you brought it back, and promoted upcoming stories/videos)

Camera work, editing, it was all great, big props

If he says he uses it, I've got no reason to question that.

If he has not made such a statement, then there's water in the can, and a loose bolt on his steerer clamp.

Of course, and I certainly wouldn't think that! There was a time when some people regarded front suspension as a crutch for weak riders. Then the same about rear suspension. Then tires wider than 2.5". Some people will always convince themselves they're the baddest badass that ever ... assed? The rest of us can enjoy bikes that feel better and go faster.

Do they have any solid examples of self-centering devices in other common applications? Because I'm pretty sure most of it in a car comes from steering geometry (caster), not any kind of active, or reactive, device. Same with a bike: trail makes bicycles self-center already. With boats... you don't really want a boat to self-center, because turning inputs often need to be held, and "centered" is rarely truly centered because of winds and currents and waves.

This [re]active device is trying to provide the feeling that the caster effect from trail is higher than the actual geometry would provide. If you like/need/want more caster effect but don't want to get it by reducing fork offset (also less wheelbase, and less flop?), or slackening the head angle (also more wheelbase/FC, and more flop?).

Except when it rebounds fast, you hit that second edge with the fork more extended, and that means the spring is providing much less force, that should feel _less_ like getting double-bounced. The _wheel_ might feel like it's getting bounced since it's making long fast moves, but not you.

Having a ride around let's do many more riders feel the joy of that trail, rather than the elitist concept that unless you can send that single double black gap jump you should miss out on the 2 miles of no jumps on the trail.

Just something to think about.

Did they really write that? Embarrassing, because it is false. None of those other types of vehicles typically have devices to self-center the steering. Cars and trucks (and bikes) steering geometry is set so that forward motion tends to center the steering. Air and water flow act to center airplane and boat rudders.

My take away is Henry got seasick riding his bike.

I'm not sure what any of that means, I'm just being a nerd.

Go back to your velocipede ya luddite!

Velocipede = An early bicycle propelled by pushing the feet along the ground while straddling the vehicle.

Luddite = one who is opposed to especially technological chang.

Does that help?

I attended a talk by him once at my uni. What I got from it is that the front basically moves sideways to correct lean faster than the rear (including rider) falls over and this is what stabilizes the bike.

If it seems to have become offs, loosen the bolt, center the bars and tighten that bolt.

Maintenance? Quite literally none.

What am I missing here?

Sure, it might not be a useful piece of tech for you but to say it would be a problem from either an owner or professional bike mechanic seems silly.

Other than that one very specific situation, KIS seems like a solution looking for a problem.

Go to Whistler for a week. You'll get better.

Hopefully you don't take criticism of the system as criticism of the write up, plus you never know with this stuff, you may have the last laugh....

The idea of a steering damper, Henry sending me to sleep or Henrys fork setup (you have paid for the travel, use it)!

I feel sorry for Henry having to make a 15 minute review about this idea....

The video started about the riding 2 bikes back to back, I really wanted to see some riding comparison between the 2 bikes, up something janky, but it never happened.

Or another axle / wheel standard.

Also read the whole article thinking "ok we have dampers and we have springs, and we hate both of them when they're not paired" and thought that describes pretty much all suspension systems. Why not try both, and maybe even... tune them?

You need that because otherwise the reach becomes insane. The radius of the arc that the contact patch moves on would not be much larger than on a traditional system, it would be equal to the trail, but the arc would be purely horizontal.

Also climbing super steep & tight switchbacks where the front wheel needs to take a higher line - then the rear tracks lower in the corner- wouldnt this just force you to under correct and push the rear wheel high? I could see it being a burden on threading big babyheads as well where you need to twitch at low and higher speeds. Sounds better for cruising buff deer trails - not the North Shore.

The solution is not making this useless piece of shit system, but rather giving your customers better bike purchase advice.

Out of context this brings a whole new meaning to KIS(s)

0mm ESL is where it's at.

You can, or you must?

This seems like a Hopey but much crappier, and much more annoying to deal with.

youtu.be/bbE3ZMj0dyI?si=5Ku8Z7KwhAHGgwTs

enjoy

velo-orange.com/products/vo-wheel-stabilizer

www.pinkbike.com/video/580599

This analog system is so 2008...

I'll see myself out now.

Not sure how many two-handed people are using them though

Late to the game, ya wads

something British undoubtedly.